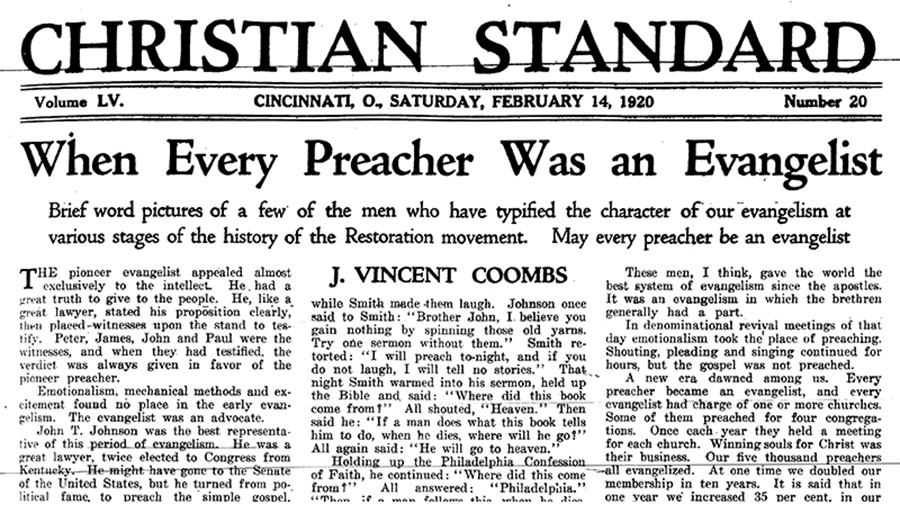

When Every Preacher Was an Evangelist

Brief word pictures of a few of the men who have typified the character of our evangelism at various stages of the history of the Restoration Movement. May every preacher be an evangelist.

Feb. 14, 1920; p. 1

By J. Vincent Coombs

_ _ _

‘Thirty Years an Evangelist’

[AUTHOR’S BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION]

In introducing our first essayist this week, we . . . include, without the writer’s permission, a personal word concerning his own career in the evangelistic field, which, we feel sure, will enhance the value of his message to all who read it:

“It has been my delight to spend thirty years in doing the work of an evangelist. I have visited every State in the Union; crossed the continent eight times; conducted one hundred revival meetings in Indiana—thirty each in Illinois, Missouri and California; added to the church eighteen thousand people, and out of that number one hundred are now preaching the gospel. One year I preached every night but seven; I preached 192 nights in succession. I think, in point of continuous evangelism, I hold the championship. S. M. Martin is the only man now evangelizing regularly who was in the field when I began. In these thirty years of evangelism, I have met with some failure, but with much success. I have felt some sorrow, but far more joy. The evangelist is an optimist. He counts it all joy to be used for the kingdom.”

[ARTICLE]

THE PIONEER EVANGELIST appealed almost exclusively to the intellect. He had a great truth to give to the people. He, like a great lawyer, stated his proposition clearly, then placed witnesses upon the stand to testify. Peter, James, John and Paul were the witnesses, and when they had testified, the verdict was always given in favor of the pioneer preacher.

Emotionalism, mechanical methods and excitement found no place in the early evangelism. The evangelist was an advocate.

John T. Johnson was the best representative of this period of evangelism. He was a great lawyer, twice elected to Congress from Kentucky. He might have gone to the Senate of the United States, but he turned from political fame to preach the simple gospel. Whether he preached to thousands in the groves or city halls, or to ten or twelve persons in a schoolhouse or home, his manner was like a lawyer before the jury, pleading for the life of his client.

He would state his proposition, and then endeavor to make it plain to all. He would then say: “How many understand this? Those who do not see it yet, raise their hands.” If hands went up, he simplified his arguments. Then he would reach the climax and say: “If you now comprehend, will you not have the courage to accept? All who accept Jesus, rise.” He would go to different parts of the house and take confessions. He would then start a new line of argument, and go through the same process. Often he would continue the service for two hours without song or exhortation. Many times, every one not of Christ, in the audience, would obey the gospel. Johnson was dignified and solemn.

His co-worker, John Smith, was just the opposite. Smith was a wit, and his illustrations were sometimes homely, but they were pointed. He preached the gospel as clearly as Johnson.

Walter Scott preached a great sermon in Kentucky, and, at the conclusion, said: “I would urge upon every preacher, when he baptizes a candidate, to place his hand upon the person, and say, ‘I now pronounce you a Christian.’”

There was profound silence. No one wanted to take issue with scholarly Scott. Finally, John Smith unwound himself, and said: “When me and my wife were married we were very ignorant. She was ignorant, and I was ignorant, and don’t you know, when our first baby was born, we were such fools we did not have sense enough to name it Smith.”

Some one tittered, and then another, and finally the audience was in a roar of laughter. Scott saw the justice of the criticism, and joined in the laugh. Everybody knew the child was Smith without announcing it. All saw that when a man obeyed the gospel he was a Christian without announcing it. Scott’s theory was dead.

Johnson was always solemn, Smith full of fun. Johnson made his hearers think, Walter Scott appealed to their emotions, while Smith made them laugh.

Johnson once said to Smith: “Brother John, I believe you gain nothing by spinning those old yarns. Try one sermon without them.” Smith retorted: “I will preach to-night, and if you do not laugh [during it], I will tell no [more] stories.”

That night Smith warmed into his sermon, held up the Bible and said: “Where did this book come from?” All shouted, “Heaven.” Then said he: “If a man does what this book tells him to do, when he dies, where will he go?” All again said: “He will go to heaven.”

Holding up the Philadelphia Confession of Faith, he continued: “Where does this come from?” All answered: “Philadelphia.” “Then, if a man follows this, when he dies, where will he go?” With one accord the audience shouted: “He will go to Philadelphia.” All laughed, Johnson with the others. With all gravity Smith turned to Johnson and said: “Brother, you told me you would not laugh to-night. I think I will preach in my own way.” Johnson said: “Go on, Brother John, I will listen.”

EVERY PREACHER AN EVANGELIST

This intellectual evangelism continued up to the war between the States. Then every preacher became an evangelist. All sought to establish the Restoration cause.

These men, I think, gave the world the best system of evangelism since the apostles. It was an evangelism in which the brethren generally had a part.

In denominational revival meetings of that day emotionalism took the place of preaching. Shouting, pleading and singing continued for hours, but the gospel was not preached.

A new era dawned among us. Every preacher became an evangelist, and every evangelist had charge of one or more churches. Some of them preached for four congregations. Once each year they held a meeting for each church. Winning souls for Christ was their business. Our five thousand preachers all evangelized. At one time we doubled our membership in ten years. It is said that in one year we increased 35 percent in our membership. It is easy to see how this could be done when each of the five thousand preachers held a meeting.

They did not have great numbers, usually from twenty-five to one hundred additions to the church membership. But these converts were in earnest, and went about to make other converts. No congregation waited for the evangelist.

True, some of the men preached all the time. . . .

They worked in a narrow circle. They did not hold one meeting in California, and the next in Ohio, but realized that a meeting in one neighborhood made it easy to hold another in the next county.

J. M. CANFIELD

Of these ministers who preached all the time in one community I hasten to mention J. M. Canfield, and his companion in the gospel, L. C. Warren. When I returned to my country home in Indiana, after teaching in another State, I heard the people talking of a wonderful preacher, J. M. Canfield. There had been one hundred additions to a church in a small town near[by], and the meeting was still in progress. One hundred accessions in that day was a big meeting. I decided to hear him.

I rode alone on horseback eight miles. I had been teaching elocution and studying oratory. I went to learn Canfield’s power. I went into the church about dark, and the house was filled. The congregation was singing “Shall We Know Each Other There?” The sacredness of the song impressed me.

Canfield went into the pulpit quietly, and began to preach John 3. He read slowly and in a low tone. He never moved from his position, and made few gestures. I asked myself where his power came from. I heard no oratory or great reasoning. He opened the sermon by saying: “There are three salvations mentioned in the Bible. The physical, eternal and salvation from sin. We have nothing to do this evening with the first or second. It is the salvation from sin that I am concerned about to-night. When I am done you will know what to do to be saved.”

Then he began to cluster passages of Scripture in such a logical way that I forgot the man—I saw the way as I had never seen it before.

His simplicity charmed me. I said to myself: “If I were not a Christian, I would go now.” Walking out of the pulpit as a teacher would step before his class, he asked all who wanted to enlist under the banner of the cross of Christ to come forward. A goodly number responded. On my way home I decided that the power of Canfield was in the simplicity of his preaching and his Biblical exposition. All of our preachers in those days were expository in their sermons. Canfield was not only a great preacher, but a good man. His children are all earnest Christian workers.

LUKE C. WARREN

Co-worker with Canfield, and working in the same territory, came that eccentric preacher, L. C. Warren. He differed from Canfield as the gentle rain differs from the hurricane. He was dramatic, sometimes bordering on the tragical. He was straight as an arrow, tall, and flexible as a rattan. He would strike an attitude, lift his right hand towards the skies, place the fingers of his left hand on his lips, then bound forward until his long black hair, as glossy as a raven’s wing, would almost touch the floor. He would swing from side to side, and then quickly assume an erect position, and the next moment would stand before his audience as a polished orator.

He was eccentric in the extreme. Once while he was preaching a dog ran across the pulpit. The small boys giggled, but Warren took no notice. In a few minutes the dog came on a return trip. As it passed, the speaker caught it by the neck, dashed it through the window, taking sash and glass with it. Yet he never varied one sentence in his discourse.

A church where he was preaching neglected to keep the house in good order. It was in the days of the old coal-oil lamp. In the midst of his sermon he paused and said, “Brother Carter, can you get me a gun?” In surprise the deacon asked: “What for?” “I’d like to shoot a hole through the lamp chimney to let a little light out,” replied Warren. The women cleaned church the next day.

There is not a church in Indianapolis, or for one hundred miles west, but that has been blessed by the work of one or both of these men.

When the evangelistic season was not good, Canfield organized Sunday schools and churches, and Warren builded man churches, working with the men, hewing logs and driving nails.

The two men not only left an influence that was felt through the land, but both left Christian children to continue the work which they established.

TEAM EVANGELISM

The next phase of evangelism among our people was the team or company plan. Groups of singers, personal workers and preachers combined their efforts. The work became spectacular, and it attracted attention. This system had some advantages. The large troupes secured an attendance and reached large numbers of people. The preacher, with his team, could enter a city and get a hearing. Many men will not join an enterprise unless it is large and has prominence. Business men freely entered into the work of the big meeting.

The system had its defects as well. The desire for numbers not only obsessed the evangelist, but congregations and church boards caught the contagion, and unless the church could secure a big troupe, it would have no meeting.

Congregations waited three and four years for the team. All this time there was no moving forward, no effort to win souls, simply waiting for the big meeting.

Instead of every preacher an evangelist, we had professional evangelists only. Some of these evangelists were engaged two and three years in advance. I myself had contracts two years in advance.

During these waiting-times the church became stagnant. Then came the spectacular show, and the collapse that followed. Under this plan, we as a people increased but little. I think now there is a tendency to return to the system of every preacher an evangelist.

Danville, Ind.

Interesting. I think we got off track when we began giving young preachers the idea they were “pastors” and lost focus on evangelism.