Training pastors is difficult work.

Training enough of them to meet the growing need for preachers and teachers of the gospel is even more challenging.

Christian Standard gathered graduation data about the largest colleges and universities in the Restoration Movement to determine how many ministry graduates they are producing each year.

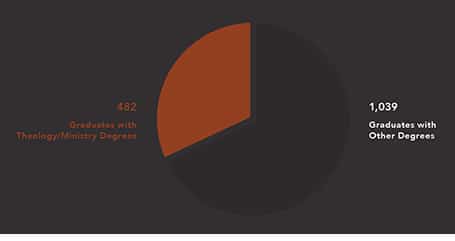

The most recent numbers from the National Center for Education Statistics show 16 Restoration Movement schools during the 2019-20 school year graduated 482 bachelor’s degree students with ministry or theology degrees.

Presumably, most of those graduates had their sights set on joining the staffs at the more than 5,000 independent Christian churches and churches of Christ in the United States.

So, are those 482 graduates enough? If the colleges produce that number year after year, can they meet the need for Restoration Movement pastors?

“Absolutely not. It’s not enough,” said Ron Kastens, director of the Ministry Leadership Program at Milligan University.

He’s not alone in that opinion.

“I get way more calls from churches looking to find ministers than I have names to hand out,” said Matt Proctor, president of Ozark Christian College.

And that doesn’t take into account the number of new churches that need to be planted.

“We need a whole lot more graduates,” Proctor said.

WHAT’S THE PROBLEM?

Christian Standard interviewed 12 presidents from Restoration Movement colleges about the ministry pipeline flowing through those institutions.

Colleges have endured more than a decade of steady declines in the number of ministry graduates they are producing.

The 482 graduates from the 2019-20 school year are the fewest they’ve produced in any of the past 20 years—down 41 percent from their high-water mark in 2006-07. That year, those same colleges produced 828 bachelor’s level ministry graduates.

Those numbers only consider graduates from schools still in existence. Cincinnati Christian University and Nebraska Christian College shut their doors in 2019 and 2020, respectively.

Generally speaking, these are tough times for Christian colleges.

David Fincher, president of Central Christian College of the Bible, said colleges continue to be affected by a downward trend in students that began during the economic downturn of 2007.

Many families have tightened their spending as it relates to higher education, eschewing private Christian universities in favor of less-expensive options. And more students who venture toward Bible colleges are doing so after they’ve already gotten a year or two of school under their belt at a community college.

Online education has exacerbated financial stress on colleges, Fincher said, as students pay less to pursue that option.

“They usually don’t stay as long and they don’t pay as much,” Fincher said.

Additional factors have also put a crimp on the number of ministry students being trained, college presidents say.

Colleges need to do a better job recruiting students of all ages. They need to do a better job of serving nontraditional and mid-career students who enter ministry later in life.

And families need to do a better job of encouraging their children to consider a career in vocational ministry.

Finally—and perhaps most important to most college presidents—Restoration Movement churches are not sending students to the colleges as they did in the past.

Derek Voorhees, president of Boise Bible College, said the colleges exist solely to help the church. They are “bridesmaids” to the “bride” of Christ, he said.

“We own what we can own, but the bride also has some things to own,” Voorhees said.

Jesus said the harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few.

Said Voorhees, “We love to recruit the few. But there are few.”

The presidents say Christian colleges face several key challenges to increasing the number of students graduating with ministry degrees. Among them . . .

A Shortage of Timothys

The shortage in true “sending” churches was forefront in the minds of many college presidents.

John Jackson, president of William Jessup University, said the church is facing a “crisis” in that it is not calling enough people into vocational ministry.

“I don’t think it’s we’re not training enough,” he said. “We’re just not calling forth enough.”

Kevin Ingram, president of Manhattan Christian College, echoed that.

“I haven’t heard a church talk about a Timothy in a long time,” he said.

Churches used to bring vanloads of students to Christian colleges, he said. A group might have visited Manhattan Christian College, Nebraska Christian College, and Ozark Christian College on the same trip.

That rarely happens now.

“We’re now having to work to get into those churches,” Ingram said.

Several college presidents recounted their own stories of being encouraged by their home churches to enter the ministry.

Ingram remembers coming home from Bible college regularly to play golf with a church member. The man regularly tucked “a little Coke money” into Ingram’s shirt pocket—enough to pay a good portion of his college expenses.

Terry Allcorn, president of Kentucky Christian University, also said his home church encouraged him to become a pastor. He followed the calling and was accepted as a student to KCU before he ever even met a college recruiter.

He said he didn’t even know there were college recruiters.

“I thought the local church did that,” he remembered thinking.

Students Not Being Encouraged to Pursue Ministry

Young people simply aren’t as interested in traditional, full-time ministry, said Paul Alexander, president of Hope International University. And churches are not challenging them like they did a couple of generations ago—when a pastor might pull a young person aside and encourage the pursuit of ministry.

“That was just part of the culture back then,” Alexander said. “I’ve talked to a lot of pastors. It’s not a part of the culture anymore.”

Part of the problem is a reluctance to guide adolescents in “strong ways,” Alexander said. Parents and pastors are less likely to try to influence a young person’s career choice.

And encouraging people to enter the ministry just isn’t on the radar of many churches.

“I would 100 percent say that churches also need to wave the banner for vocational Christian leadership,” said Proctor, of Ozark Christian College.

Churches use a variety of metrics to determine how healthy they are—from attendance to baptisms to small groups to giving. They might add a metric to measure how many young people have gone into ministry from that church, Proctor said.

“There are places where they’re doing a great job, but there are definitely places where that’s not put in front of young people,” he said.

And in some places, young people actually are discouraged from pursuing ministry careers.

Larry Carter, president of Great Lakes Christian College, spoke last year at a large church in Michigan and asked to speak to the high school Bible class. The youth minister, himself a GLCC graduate, reluctantly agreed.

Carter said he talked to 40 or so students about how his own Bible college education changed his life.

After he finished—and in front of the class—the youth minister said Carter may have seen glazed looks on the faces of the students because “I discourage anybody from going into ministry.”

The explanation: Ministry is hard.

“I was like, holy cow!” Carter said. “No wonder we’re not getting anybody from this church.”

Pastors Who Are ‘Frustrated and Burdened’

Some college presidents recognize the culture—and church ministry—has changed.

Ministry is not the esteemed profession it used to be. The pay isn’t great. The hours are long. And some churches don’t treat their pastors well.

And some parts of the country are highly secular. Churches have a hard time just building their youth programs—much less raising up future preachers.

Boise Bible College tries to recruit students in Washington and Oregon, but Vorhees said it has been tough sledding.

John Jackson, of William Jessup University, said pastors—like people in many professions—can be burdened with the condition of their vocations.

“They are frustrated and burdened,” Jackson said. “We’ve had what I would call the professionalization of pastoral ministry. And that professionalization has often meant the burden of leadership falls more singularly on a solo individual.”

It’s natural then that those pastors might not suggest others follow their path.

Parents Who Talk Students Out of Bible College

Christian parents often aren’t much help. It isn’t uncommon for them to dissuade their kids from entering the ministry, college presidents said.

Kastens, of Milligan, said parents used to be concerned mostly about their children becoming missionaries and serving in some remote, faraway location.

“Now it seems like parents are not encouraging their children to go into ministry period,” he said.

MCC’s Ingram remembers having a hard conversation with his father before heading off to Bible college. But overall, Ingram’s father was happy about his son’s choice to pursue the ministry.

Today, fewer parents are happy about it.

Silas McCormick, president of Lincoln Christian University, said he sometimes sits down with parents concerned whether their kids will be able to receive fairly normal job benefits—like health insurance. Of course, many churches don’t provide benefits.

That wasn’t a discussion just 20 years ago. But factors like that one can cause a parent to dissuade their child from entering the ministry.

The college feels the effects.

“It’s harder and harder to find students every year who have a deep commitment to ministry,” McCormick said.

A Lack of ‘Brand Loyalty’

Carter, president of Great Lakes Christian College for more than 20 years, identified a related challenge. He said he’s seen a change in what he calls “brand loyalty” to the Restoration Movement among churches during his time at GLCC. It’s a “huge decrease,” he said.

“The church members aren’t identifying themselves as Restoration Movement people,” he said.

As a consequence, they aren’t prioritizing sending their children to Restoration Movement colleges.

Of course, the “brand loyalty” question swings both ways, said David Fincher, of Central Christian College of the Bible.

Sometimes, colleges recruit students who have Christian backgrounds outside the Restoration Movement, and those students fall in love with the independent Christian church while in school.

Fincher said it happened to him. He grew up a Methodist.

“We get those people all the time. I love it when I see that happen,” Fincher said.

And, so, there is no uniform kind of student among Restoration Movement colleges and universities. In fact, some students come with no faith in Christ at all.

Dean Collins, president of Point University, said he wouldn’t be surprised if 30 to 50 percent of his student body came from a non-Christian background. The college, then, becomes the primary point of discipleship for those students.

“That’s a very different job,” he said. “It’s a harder job, but it’s an essential job.”

Churches That Send Money but Not Students

Some churches try to help the colleges by sending money. This is a long-standing tradition in many congregations.

College presidents were quick to express appreciation for that support. Even during the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic, when many church doors were shuttered, monthly financial support from the churches continued.

However, “the greatest gift the churches can send us is a student,” said John Maurice, president of Mid-Atlantic Christian University.

The financial benefit of a single student deciding to attend the college usually far outpaces the monthly support any one church may give, Maurice said.

But some college presidents worry churches simply figure their financial gifts are enough.

KCU’s Allcorn said he regularly visits churches to thank them for their gifts. But, he said, “If I’m feeling cantankerous, I might say we don’t exist just for you to send us money . . . we exist also for you to send us students.”

On either count—financial gifts or student recruitment—some presidents noted that churches can’t be expected to continue their support without regular interaction from the colleges.

Pastoral turnover can be high, and the colleges need to make sure they visit those churches to build new relationships so the financial pipeline will remain open.

“I think it is a matter of getting on people’s radar,” Allcorn said. “I think it’s important to maintain those relationships.”

Believing the Worst

As college presidents have worked to connect—or reconnect—with the churches they serve, some say they occasionally encounter a subtle distrust.

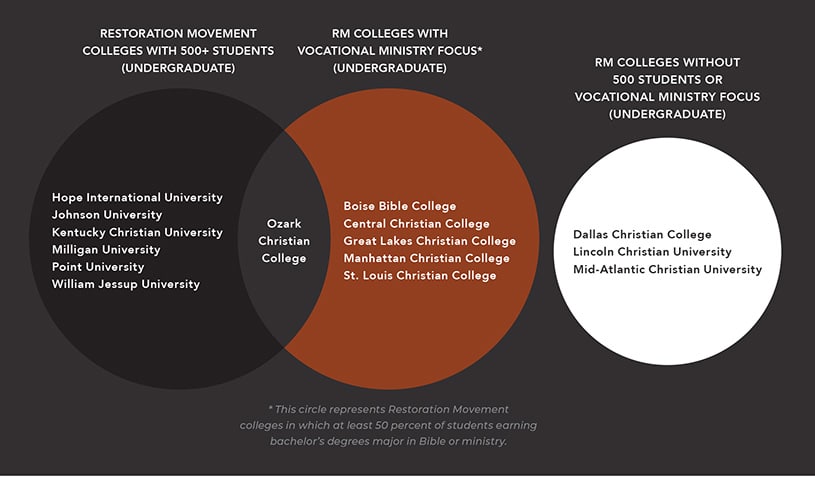

Sometimes, it’s the result of the colleges’ decisions to offer more than just ministry training to their students. Most colleges operate with a wide range of degree offerings. Training preachers isn’t necessarily the primary mission. (See sidebar, “Two Christian College Models,” at the end of this article.)

Maurice said Mid-Atlantic Christian University once was accused of dropping its preaching program altogether. It wasn’t true.

This perception can affect funding. Some churches are reluctant to support a college because they don’t want to be funding sports scholarships instead of young preachers.

“It’s a sad day that so many of our churches look only at the value in Christian higher education as [solely] producing preachers,” Maurice said.

Maurice said he’d like to educate more preachers. But a 2,000-member church may have only five paid staff members. And Christians are needed in every vocation.

“Who really is influencing more people. Is it the five or is it the 2,000?” he asked.

Allcorn, at Kentucky Christian University, echoed that.

“We cannot surrender our education to the secular university,” he said.

And besides, Allcorn said, those non-ministry graduates aren’t necessarily lost to vocational ministry. He knows of one business graduate from KCU who serves as a pastor in an executive role at a local church. And he knows an education graduate who is serving bivocationally at a church.

Brian Smith, president of Dallas Christian College, said surveys over the past three years show 55 to 60 percent of DCC’s graduates are planning to go into vocational ministry.

“Not nearly 55 to 60 percent actually graduate with a ministry degree,” he said. “I don’t know that the degree they report to have graduated with tells the whole story.”

But the occasional distrust can go beyond college program offerings. It also can be rooted in theology.

GLCC’s Carter told of a rumor that spread that he no longer adhered to the Restoration Movement’s beliefs about baptism. He had to visit a local association of pastors to clear the air, and he received an apology.

Carter said similar dustups have occurred over women’s roles in the church and the role of Moses in authoring the Pentateuch.

“Especially on the conservative side, we have such a willingness to believe the worst about our Bible colleges,” Carter said.

HOW DO WE MOVE FORWARD?

Facing those headwinds, Christian colleges are trying to find their way forward.

Even as some doors seem to be shutting—or at least aren’t open quite as wide as they used to be—other possibilities are appearing. Here are five examples.

A New Ministry Pipeline

McCormick, of Lincoln Christian University, said he sees two ministry “pipelines” rather than just one.

The first consists of 18- to 22-year-olds who go straight to Bible college and then into ministry. The second consists of second-career adults who opt to enter the ministry after working for years in other vocations.

That second pipeline, some college presidents say, tends to be a bit more robust than the first.

“One is easy to sell, and one is hard to sell,” McCormick said.

Second-career students oftentimes are more committed to their decision to enter ministry before they even seek out a college to attend. They’ve already weighed the costs and benefits, he said.

CCCB’s Fincher said a growing market for Christian college recruits consists of people over the age of 26. Those ministerial candidates are most influenced by their spouses and preaching ministers, rather than their parents.

“That’s where the sweet spot is going to happen with that market,” Fincher said.

A New Paradigm

And, so, colleges and churches are adapting.

Many larger churches have gravitated toward hiring pastors from within their congregations—taking someone who is in mid-career and putting them into a pastoral role. Rather than sending those new staff members to a Bible college, the churches are training them on their own.

Some churches have created entire training programs or residencies to equip new ministers. And some are finding it necessary to call in the Bible colleges to help with that, particularly in the more technical areas of biblical studies and theology.

Colleges are increasingly linking up with churches to help.

Lincoln Christian University announced in September it is partnering with The Merold Institute of Ministry, a training program at Harvester Christian Church near St. Louis.

Great Lakes Christian College is partnering with 2|42 Community Church in Brighton, Michigan. The college will send one of its professors—in New Testament, Old Testament, and theology—to work with the staff at 2|42.

Boise Bible College is looking to provide a remote training program for students who want to bulk up their pastoral skills without leaving their home churches. BBC’s model would pair a student with a mentor in his or her home church—likely the pastor—and then run the student through a remote curriculum.

Hope International University has a program called SALT—School for Advanced Leadership Training—that it has deployed at about 30 churches; SALT blends the school’s online education with on-the-ground mentors from the churches.

Dallas Christian College has created an academy at Compass Christian Church in Colleyville, Texas, that awards certificates in biblical studies. Thirty-five students are participating, most of them staff or key volunteers at the church.

Partnerships That Work

Smith, of Dallas Christian College, said some large churches try to go it alone in creating training programs for their staff and volunteers—only to think twice about it and seek out help from a college.

“Many walk into [the process] and say, ‘Oh gosh, this is more complicated than we thought,’” Smith said.

The difficulty in all of this, said HIU’s Alexander, is figuring out a way to blend the very targeted goals of a church’s ministry training program with the requirements of a college. The church usually knows exactly what skills and knowledge it wants its program to provide—no more and no less.

The college, meanwhile, must think about its accreditation standards. It’s an opportunity for colleges to educate students in new ways, but it’s a challenging one.

“It is a challenge to make triangles and squares fit together,” Alexander said. “If we can figure that out, we can provide a really strong bridge so that everybody wins.”

LCU’s McCormick said some nontraditional students balk at the expense of pursuing a 36-credit hour master’s degree program. But they may be willing to pursue a more affordable certificate in biblical studies. Whatever the case, the students benefit from their studies, he said.

Fincher, of Central Christian College of the Bible—which has multiple partnerships with local churches—said a Bible college can add academic credentials to a megachurch’s in-house ministry training program, and that can give the program more credibility with trainees. Adult learners still want an educational program that is serious, even as they look for something that’s affordable.

A program must be so worthwhile a person will forgo family time to pursue it.

“It takes an academic partner to push it over the edge as a worthy investment,” Fincher said.

Education Reverting Back to the Churches

In all of this, some college presidents see pastoral education moving full circle.

Fincher said 200 years ago, ministers weren’t trained until after they had obtained higher education in some other discipline, such as Latin or Greek. After that, they were paired with a minister for practical training.

Not until the late 1800s did the current model of Bible colleges and seminaries take hold.

“Education is going back to the church,” Fincher said. “That’s where it started.”

Along these lines, some college presidents said it’s wrong in some ways even to ask whether Restoration Movement colleges are producing enough ministry graduates.

Point University’s Collins said the job of developing pastors historically has fallen to the churches themselves. Leadership in the early church was typically homegrown and bi-vocational.

“It’s a little awkward or odd to me—someone comes to a Christian university, and we’re supposed to be the ones who disciple them and point them back to their place of origin,” he said.

The Restoration Movement historically has valued the concept of the priesthood of all believers, he said. The churches have an obligation to disciple their members, and Christian colleges ought to disciple whoever comes to them—whether they want to be a vocational pastor or not.

“I do think some of it goes pretty deep in our theology of ministry and, in particular, the whole distinction around—to use those ancient words—the clergy and laity,” Collins said.

Meanwhile, Jackson, of William Jessup University, said he believes the Restoration Movement’s founding ideals—believing in the lordship of Christ, the authority of Scripture, and the unity of the church—are now pervasive in much of the evangelical world.

“I believe the Restoration Movement has won,” he said.

As such, many Restoration Movement churches are satisfied hiring pastors who emerge from non-Restoration Movement colleges and seminaries, so long as those schools are broadly evangelical in what they teach, Jackson said.

That doesn’t negate the fact the church still faces a struggle in finding qualified pastors.

“I think we have a crisis in the church in that we’re not calling forth people who have a call to vocational ministry,” Jackson said.

A Focus on the ‘Front Side’ of the Pipeline

Perhaps lost in the paradigm shift that is putting more attention on nontraditional ministry students is the continued need for colleges to recruit high school students into their programs.

Those high school students continue to be harder to find. But Kastens, of Milligan, has seen something that gives him hope.

He recently visited West Side Christian Church in Springfield, Illinois, which has launched a ministry apprenticeship program for high school students.

Those students work a few hours in ministry during the week for the church and get involved with the church’s staff. Not all of those students are likely to become vocational ministers. But some might.

And, so, while more churches are launching formal residency programs for postgraduate and adult learners, they also should be considering how to promote the ministry to their youth.

“It would be great if more churches could give similar attention and energy to the ministry pipeline on the front side of college,” Kastens said.

“If we don’t understand that the solution to our minister shortage begins in middle and high school, it will not matter how great our colleges and residency programs are. And that’s on us. It’s on adult Christians who are a part of a local church.”

Chris Moon, a pastor and writer living in Redstone, Colorado, conducted interviews and wrote this article. Kent Fillinger helped with research.

Download a PDF of the charts, Jan-Feb 2022 College Charts

_ _ _

— SIDEBAR —

Two Christian College Models

Restoration Movement colleges and universities come in a couple of varieties.

Some offer a wide range of degree programs, from nursing to business to engineering. They still offer ministry programs, but those aren’t the primary mission of those schools.

These colleges have opted to broaden their approach—and their enrollment—to raise up Christian leaders across a spectrum of secular vocations. After all, the world needs more people with Christian worldviews in every vocation, college presidents say.

But a handful of Restoration Movement schools have opted not to pursue that model. They simply want to train ministry leaders.

These include Boise Bible College, Central Christian College of the Bible, Manhattan Christian College, Ozark Christian College, and St. Louis Christian College (which is in merger talks with CCCB).

Presidents at these institutions say they take nothing away from their peers with broader program offerings. A student may come into a college looking to major in business or biology and then decide they want to be a pastor—because that degree program also is offered there.

“I don’t think that’s a terrible strategy,” said David Fincher, president of Central Christian College of the Bible.

And a non-Christian might head to a Christian liberal arts college and find Christ in the classroom—because many of those schools are populated mostly or almost entirely with Christians.

Dean Collins, president of Point University, said his college sees students baptized each semester.

Further, some colleges with broader degree programming pair a non-ministry degree with a minor in biblical studies or some other Christian discipline. So those students are prepared to impact the world for Christ in a number of ways.

While some of the presidents of the more traditional Restoration Movement “Bible colleges” say they can’t criticize the liberal arts approach, they still point to the advantages of their model.

“We’re probably going to die on that hill,” said Derek Voorhees, president of Boise Bible College, which graduates only students with ministry degrees of some kind.

He said the ministry-intensive model has proven effective.

Since 1990, nearly 80 percent of BBC’s graduates have remained in church ministry for at least five years, and that doesn’t count students who go on to seminary or head to the mission field, Voorhees said.

“That’s a pretty decent track record of hitting our objective,” he said.

The benefit of maintaining focus has other advantages.

Matt Proctor, president of Ozark Christian College—the largest Restoration Movement school exclusively focused on raising up ministry leaders—says every student in any class at OCC is aiming to enter the ministry in one way or another. And that leads to a better, more focused ministry education.

“There’s a commonality of purpose,” he said.

It also helps in connecting with—and raising money from—churches across the Restoration Movement. Some college presidents say they’ve noticed more distance recently between them and the churches they serve, for a variety of reasons.

But Proctor said he’s sensed OCC’s relationship with churches strengthening in recent years, particularly after the closures of Cincinnati Christian University and Nebraska Christian College. Those have opened some pastors’ eyes to the need to support their local Restoration Movement schools.

OCC recently launched a $5.9 million capital campaign. Already, $4.7 million of that has been raised, thanks to some large church gifts. For instance, Southeast Christian Church in Louisville gave $1 million.

Churches like Southeast, Proctor said, have appreciated OCC’s focus on ministry and its avoidance of any “mission drift.”

“I’ve heard that from other megachurches, too,” Proctor said. “I hear that from smaller churches. We’ve never had an identity crisis.”

—C.M.

Download a PDF of the charts, Jan-Feb 2022 College Charts

I just began my 43rd year in ministry. There was a time when the church I served, sent 18 students to Bible College. 14 of them graduated & entered ministry or missions. Only 2 are still serving full time. 1 as a missionary – 1 who has had 5 ministries in 10 years. Most had supporting parents, all had a positive youth/mission/church community and had good college experiences. What happened? My perception: some of it is related to serving in negative churches; some goes to a lack of “practical ministry preparation in college; but a lot of it centers on lack of personal discipline, attention to feed themselves spiritually; using other people’s material instead of personal study; inability to develop & implement change within the church culture and instant gratification. At the church I served for 35 yrs, I oversaw a staff of 7 ministry and 3 support. All but one of the Bible College trained staff were lazy, divisive with the elders, refused to do things asked of them, and created such turmoil in the church. As of today, 3 of them are no longer in ministry and it’s been revealed were hiding serious sin issues. And…the guy who has had 5 ministries in the last 10 years, why doesn’t someone call and ask about him before hiring him? Those of us in the RM just pass the problems and fail to confront the lack of spiritual development. For the last 7 yrs of my ministry, I’ve preached at a smaller church. I have developed and worked with a team of people, which has been a joy. I would have to take a hard look at ever hiring someone from our schools to lead ministry. It’s not that I blame the school, but it’s easier to find people from within who understand the community, the church and you can see their heart for serving.

At Christ’s Way Christian Church we are an Elder led congregation with Bi-vocational Elders who shepherd and preach. Not sure why we aren’t training Elders to lead congregations, preaching, and making disciples. Whether they are paid salaries or not we need to get away from the hired gun model.

One thing I became aware of and graduated from Bible college, and serving a short pastorate is that there was never any kind of aptitude counselling by the three colleges I attended.

After three years college, I finally took an aptitude test from a local state college, and was advised that I should be a carpenter or engineer. Under some family pressure to “press on”, I stayed in school, graduated, then had a one year pastorate, which was a bust.

I went to North American convention the summer after ending the pastorate, was unsuccessful finding a position, then moved to California to start over. I was a Good Humor man, a department store clerk, a soap sample deliverer, and finally a city bus driver for two years. During that time I had another aptitude test, which resulted with the same recommendations.

Soon after taking the driving position, I started over, taking pre-engineering courses at night, and finally took an entry level drafting job with the largest city in the area. I continued with night classes for the next twelve years, taking promotional tests and retired from the city after thirty-seven years as a licensed civil engineer.

Perhaps things could have been different if colleges and church-related groups could have have had mentoring programs–I have only been aware of them in recent decades.

Since retiring I met a classmate of my wife (they graduated from another Independent Bible college) who had a similar experience. He even went on to graduate school and served a couple churches, before recognizing his graphic arts ability and running a successful printing business. He too, felt that Bible colleges of that era were so anxious to train preachers that they ignored the interests and aptitudes of their students.

There was constant referencing of “Restoration Movement” colleges but the article is actually about colleges associated with one branch of the Restoration Movement. The largest schools offering diverse degrees would be those affiliated with the other branches of the Restoration Movement, especially Churches of Christ schools which still have strong ties with their colleges. It would be helpful to clarify this in your writing.

What is missing from this article are the many documented gap-year programs that have sprung up in both the secular and religious spheres to meet the needs of young people today. EnterMission is but one of these programs. We are a trade-school approach to Christian development blended through both classroom and experiential elements – transformational and skills-focused, we provide hands-on ministry experiences from their involvement with various ministries throughout the U.S. as well as international mission experience as they spend over 4 months overseas. During their entire year with us they are individually mentored and even have the opportunity to earn up to a semester of college credit through Johnson University. In a real sense, our young people are not only needing to be guided in how to become independent, but they are desperately seeking to understand the implications of their faith beyond the walls of the church and traditional programming. There is indeed a third option for high schoolers who are unsure of their future besides college or entering the work force. I believe that these gap-year programs will continue to grow because of this hands-on approach to life, learning and practical ministry.

The charts accompanying this article indicating “RM college with a vocational ministry focus in which at least 50% of student earning bachelor’s degrees major in Bible or ministry” fail to take into account the colleges which are ABHE accredited meaning all students take at least 30 hours in Bible/theology which is roughly the equivalent of a major in Bible.

Some of these colleges might do well to at least slow the bus down before throwing the churches under it.

This is a multifaceted problem, but the Bible college presidents crying “woe is me” and blaming churches is rather disheartening.

We aren’t addressing the fact that a Bible college degree is going to cost a preacher 80-100K by the time they are finished. I’m less than a decade removed from Bible college and most of these schools are charging 5-10K more, annually, now than they did when I entered in 2009.

But this comment from Kevin Ingram grinded my gears: “We’re now having to work to get into those churches.”

That’s false. It may not be a lie, but it’s certainly misplacing the responsibility. I work in a church with 125-150 people as an associate minister. We support two (2) of the colleges mentioned above and in the time I’ve worked here, I can count on one hand the amount of correspondence I’ve had with admissions teams or even Bible college representatives. And each of those times, I was the one who initiated contact.

I’ve called and emailed colleges asking them for promotional material for our youth area. One college (a large notable one starting with the letter “O”) has not sent any, despite multiple emails requesting it (we also support said college). So we have a few Bible colleges on my bulletin board. That particular school is not one of them.

When churches are the ones having to initiate conversations just to get your Bible college in front of their high school students, then the comment that the COLLEGES are the ones holding that burden is just not true.

As long as the Bible college presidents continue to place the blame on everyone besides themselves, this problem will continue.