By Daniel Ross

One wouldn’t think an Anglican and a member of the Church of England could have wide acceptance among the evangelical community. But few authors or theologians in the last 100 years are as widely quoted or have had as profound an influence on the American church as C. S. Lewis.

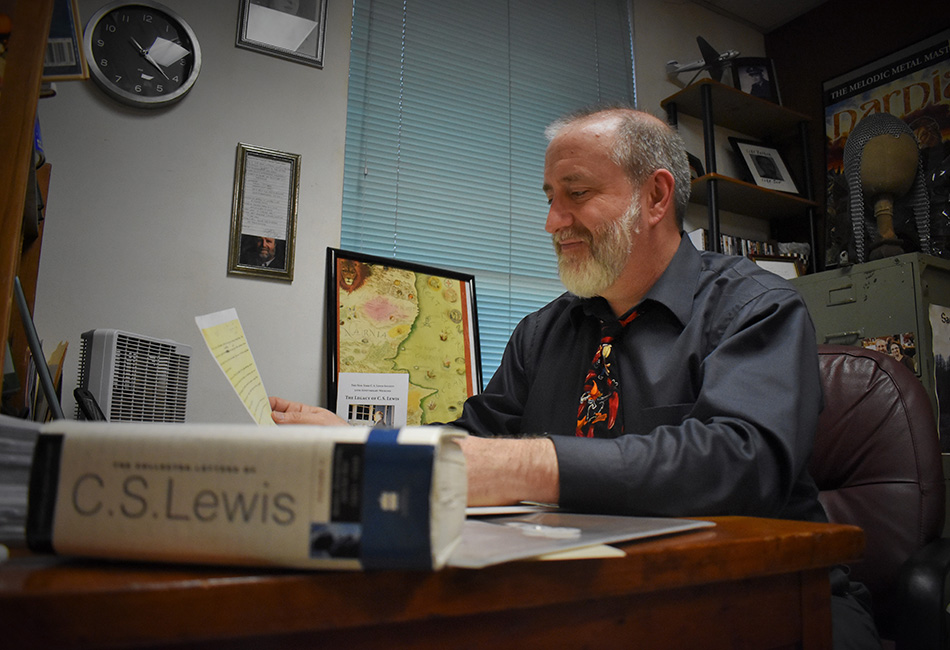

It boils down to Lewis’s ability to write with clarity and imagination, according to Dr. Charlie Starr, professor of English and humanities at Great Lakes Christian College, Lansing, Mich., and one of America’s leading experts on Lewis.

“Where most theology tends to be rather dry with abstract terms, Lewis wrote for the common man,” Starr explains. “For the education level in his day, he was writing for average folks. He was writing to appeal to their imaginations as well as their sense of reason.”

IT STARTED IN COLLEGE

Starr’s introduction to Clive Staples Lewis came by reading Mere Christianity for an apologetics class at Dallas Christian College in 1981. Starr then read a few other Lewis books—including the seven books in The Chronicles of Narnia series. Starr was pulled in by Lewis’s writing, but reading Lewis’s last novel, the more obscure Till We Have Faces, is what pushed him into a new realm of interest in the author.

“Once I got to where I was focusing more on literature and less on theology and read Till We Have Faces, I realized just how great a writer Lewis was,” Starr recounts. ”I should have realized it all along, of course. Lewis was an English professor who was just capable of doing theology. He called himself ‘an amateur’—which is hilarious.”

Lewis’s enduring status as a “patron Protestant saint”—as Starr jokingly describes him—endures because of a few factors, including the endorsement of pop culture icons like U2 frontman Bono, who included Lewis’s book The Screwtape Letters in the band’s 1995 music video for the song “Hold Me, Thrill Me, Kiss Me, Kill Me,” and via his Screwtape-esque MacPhisto stage character during two blockbuster world tours in the mid-1990s and mid-2010s.

Additionally, Lewis’s unique blending of theology and fiction in the Narnia series, subsequent film adaptations of the same, and the work of Lewis’s literary executor Walter Hooper have kept Lewis in the public eye for six-plus decades after his Nov. 22, 1963, death . . . the same day of both John F. Kennedy’s assassination and the death of Brave New World author Aldous Huxley.

However, Starr—who has authored four novels, five nonfiction books, and numerous short stories, poems, scholarly articles, and essays—takes his enjoyment and fascination for Lewis to, as he describes it, “the height of Lewis nerd-dom on earth,” with his work studying and becoming the foremost authority on Lewis’s handwriting.

A PECULIAR EXPERTISE

This fine detail of a public figure is a deep dive few are willing to take. For Starr, however, this element of his life happened “by absolute accident—some would say by providence.”

In 1977, the Lewis short story “The Man Born Blind” was posthumously published. A few years later, a manuscript copy of the story, called “Light,” surfaced—nearly 20 years after Lewis’s death.

“The ‘Light’ story is, essentially, the same story, but there are real differences. No one published the ‘Light’ version. In fact, it was owned by a man in Indianapolis named Ed Brown,” Starr says. Brown, a Lewis collector, bought the manuscript from a bookseller in the United Kingdom and, as Starr describes it, the “Light” story was shrouded in mystery.

“It was mysterious because we don’t know where it came from. It’s mysterious because it’s such a strange story, with the strangest ending Lewis ever wrote. It’s mysterious because one person accused it of being total forgery. Lewis’s friend Owen Barfield said it was written before Lewis became a Christian. Lewis’s stepson Douglas Gresham said Lewis wrote it in the 1950s after Lewis became a Christian. So, here I had this mysterious manuscript, which is now at Taylor University in Upland, Indiana, and I was given the opportunity to publish it and write a book about it,” Starr says.

“Figuring out the date for the story was very difficult. But while I was working on it—which became a book called Light: C. S. Lewis’s First and Final Short Story—I stumbled across the fact that Lewis’s handwriting changed throughout his lifetime. What I realized was if you could map out all the changes in Lewis’s handwriting, you could figure out when undated manuscripts were written,” Starr explains.

OTHER OPPORTUNITIES

Handwriting became Starr’s key to unlocking Lewis’s undated work. Once changes in Lewis’s handwriting were charted, dates could be assigned to undated documents—a treasure trove for Lewis scholars, fans, and collectors. With this new scholarship, Starr was able to determine “Light” was written in the 1940s—not in the 1950s . . . and not before Lewis became a Christian. This solidification of Lewis’s handwriting led to other opportunities to see privately-owned Lewis manuscripts, work on dating them, and more work as the “go-to guy” authenticating original Lewis documents. In addition, Starr hopes this work will lead to all of Lewis’s letters—up to 30,000—being published digitally one day.

Starr said studying Lewis’s handwriting, while “esoteric, geeky, and nerdy,” is the method to date documents when there is no other way. His work leads him to believe there are seven periods in Lewis’s handwriting. Starr described correctly identifying the varying eras clear back to Lewis at 10 years old.

Some of these periods include Lewis’s post-injury years after World War I and the latter years of his life when Lewis struggled with arthritis—though Starr says Lewis worked diligently to clean up his handwriting when responding to letters from children fascinated with the Narnia books.

It would seem conversion changed Lewis profoundly in all ways—even down to his handwriting. One of the periods Starr describes includes 1931, when Lewis converted to Christianity, and changed the way he wrote the letter g.

“In late September, early October of 1931 [Lewis] becomes a Christian. By the end of October, he has changed the way he writes the letter g. I think he changed to a new g because it looked better and because he didn’t like the way it looked when he wrote ‘capital-g’ God,” Starr explains.

“It’s like you’re solving an archeological mystery when you’re dealing with this.”

Daniel Ross serves as executive minister with Redemption Christian Church in southern Indiana.

Dr. Charlie Starr’s book Light: C. S. Lewis’s First and Final Short Story is available at Amazon.

We are excited to have Dr. Starr join the Faculty at Great Lakes Christian College. God is doing something at GLCC. He is bringing together an incredible team to train students to be servant leaders in the church and world. I pray more young men and women come to Lansing to prepare for vocational and marketplace ministries!

Fantastic article Daniel. A pleasure to read as always.

Curious about your class at Dallas Christian college— who was the teacher of your apologetics class where you read Mere Christianity? Great article!

Ruthetta Getchel our Professor in Apologetics at DCC was Robert Brokus. I took his class in 1979 and he was an excellent Professor who taught there for many years.