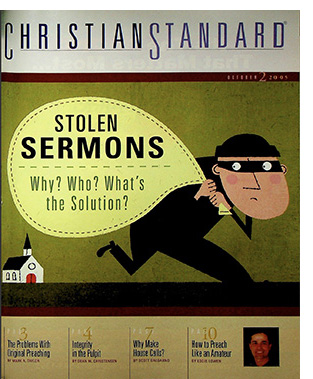

Today we feature an article from 2005 that focused on “Integrity in the Pulpit,” or more specifically, sermon stealing. Is this an issue that has gotten worse over the past 19 years?

_ _ _

Integrity in the Pulpit

By Dean M. Christensen

Oct. 2, 2005; p. 3.

I will study the way that is blameless. When shall I attain it? I will walk with integrity of heart within my house (Psalm 101:2, New Revised Standard Version).

Over the past several years, cheating and plagiarism have surfaced as hot topics in academia, the news media, and more recently, the church. Several high-profile cases involve pastors of large churches who resigned, or were fired or suspended for repeated instances of “borrowing” sermons from various sources without attribution.

In September 2004, a prominent pastor in North Carolina admitted he had plagiarized sermons during the previous two years. In his words, he had been “using sermons of some brother preachers, in part or in whole, for my sermons, and did not give them credit.” He tendered his resignation when confronted by a church leader who had heard a sermon on the radio, by a different preacher, that sounded suspiciously like one his pastor had recently preached.

The pastor of a large Presbyterian congregation near St. Louis, Missouri, resigned when church members and fellow staffers recognized some of his sermons as the work of a well-known Presbyterian minister from New York.

The rector of Michigan’s largest Episcopal parish was “inhibited” (suspended) for 90 days in March 2002 for plagiarizing sermons from an Internet subscription service.

A United Church of Christ pastor in New Hampshire resigned after an associate detected his plagiarism activity. The pastor had been using entire sermons lifted from the Internet and preaching them as his own, without attribution. When confronted, he readily admitted his wrongdoing, asked for forgiveness, and stepped down from a ministry he had held for 15 years.

Sermon “borrowing” has been going on for centuries. There is an anecdote about someone accusing Presbyterian pastor Samuel Hemphill of pulpit plagiarism in Philadelphia in 1735. Benjamin Franklin spoke in his defense: “I rather approved his giving us good sermons composed by others than bad ones of his own manufacture.”1

I broach this subject in humility because, I must confess, I am not without sin in this matter. On several occasions during my 16-year pastoral career, I “borrowed” a sermon when the well was dry, or I was worn out, or (dare I admit?) simply lazy! At the time, I gave scarcely a thought to the ethical aspects involved. Only in hindsight do I see more clearly the error of my ways.

Those entrusted with the solemn responsibility of shepherding God’s flock and who represent Christ to a watching world are called to the highest standards of truthfulness. They must be especially careful to model integrity in their personal and professional lives, including in the pulpit. As King David prayed, “I know, my God, that you test the heart and are pleased with integrity” (1 Chronicles 29:17).

PLAGIARISM DEFINED

As it applies to the pulpit, the most basic definition of plagiarism is “preaching someone else’s sermon research or content without giving public credit for it.”2 It is covert appropriation without overt appreciation.

Pulpit plagiarism can take several forms. The most blatant expression is preaching someone else’s message verbatim—or nearly verbatim—without attribution. Some would argue that simply adopting another’s outline, or basing the structure of one’s sermon on another’s sermon, is plagiarism if no credit is given for that outline or structure. Personalizing anecdotes that happened to other people, a common practice it seems, is an egregious form of plagiarism. It involves two sins: lying and stealing!

Whatever the form, there is plenty wrong with pulpit plagiarism—especially if it is habitual. One writer put it this way:

The central problem with plagiarism is twofold: (1) it is stealing; and (2) it bears false witness . . . To fail to acknowledge [the source of your words and ideas] is to give the false impression that they have originated with you. Hence, plagiarism steals from another and gives a false impression to your audience.3

WHY SOME PREACHERS STEAL SERMONS

Cheating and plagiarism are seen as grave problems in the worlds of education, business, politics, sports, and entertainment. Offenders are often severely sanctioned. At the university where I work scholastic integrity is taken very seriously. Students may be penalized with anything from an F on an assignment to expulsion from the university for submitting bogus work. How, then, can some preachers and church leaders wink at similar deception in the pulpit when even the unbelieving world knows it to be wrong?

I don’t profess to understand the deepest motives of all preachers who plagiarize. For many it may have something to do with the burden of a nearly unbearable production schedule. Ministry demands today are as great as ever. People in our high-tech, entertainment-soaked world require interesting, compelling, even entertaining messages. For some preachers, sermon borrowing—a quaint euphemism for sermon stealing—is a welcome solution to this challenge. It is a relatively quick and easy way to keep their congregation happy and their own sanity intact.

Some would rationalize that neither church members nor lay leaders think or care much about this issue. A poll of American congregations on the topic might indeed corroborate this. As long as their felt needs are being met, many people simply don’t care where their pastor gets his sermons.4 Most church members probably haven’t considered the possibility that their pastor could be pinching sermons, and some pastors take advantage of that presumed naivete. As the examples above attest, however, they do so at the risk of their careers and reputations.

Some may be motivated by a desire to be deemed smarter, more eloquent, and more profound than they are, or think they are. This is suggestive of Ananias and Sapphira, whose hunger for the applause of men led them to portray themselves as something they weren’t.

Similarly, the underlying issue for some could be a supposed lack of preaching skill. They pilfer sermons because they think they can’t prepare good ones themselves. Such individuals owe it to the Lord, their flocks, and themselves to seek further homiletical training, or maybe to explore alternate ways of fulfilling their ministry calling.

Perhaps the core issue is a faulty work ethic that bears the fruit of poor time management, procrastination, or laziness. As Timothy Merrill, executive editor of Homiletics Online, frankly declared, “Those who plagiarize their sermons have a problem with how they prepare their sermons. Truth be told, they don’t prepare.”

Ministers who are accountable to virtually no one—whose weekly use of time is a mystery to their congregations—can probably get away with cutting many corners. They cut corners in the ministry of the Word and shortchange their flocks when they fail to struggle with a passage of Scripture, internalize it, and allow it to soak into the fiber of their innermost beings. It is cheating to bypass the demanding work of exegesis and sermon construction and download a prefabricated version from someone else’s head. Those who do may be in critical need of repentance and rededication to the service of God.

A SIMPLE SOLUTION

In theory, it is very simple to solve this problem: When attribution is given, it is no longer plagiarism. There may be times when an exhausted, overwhelmed, or under-the-weather pastor will turn to the Internet, an anthology on the bookshelf, or Chuck Swindoll’s book on the nightstand for a little help with Sunday’s sermon.

That can be quite all right, as long as due credit is given. It isn’t difficult to say something like, “I am indebted to Pastor Goodsermon for the structure and much of the content of today’s message.” If it feels awkward to say this, perhaps a line in the bulletin or sermon insert could serve the purpose.

There is no universal standard with regard to when and how to make attribution. The point is, for the sake of honesty, preachers should give credit where it is due. They should keep in mind the words of wise King Solomon: “The man of integrity walks securely, but he who takes crooked paths will be found out” (Proverbs 10:9).

In our age of ethical relativism, high-profile cases of lapses in moral integrity are making headlines every day. Christian ministers are urgently needed who follow Jesus’ example of integrity in all aspects of their lives and ministries—especially in the pulpit. Paul’s words to Titus are still relevant:

In everything set them an example by doing what is good. In your teaching show integrity, seriousness and soundness of speech that cannot be condemned, so that those who oppose you may be ashamed because they have nothing bad to say about us (Titus 2:7, 8).

_ _ _

1Quoted by Lugene Schemper, “Sermons on the Web,” Banner of Truth, 2003; available at www.banneroftruth.org. [Link is now outdated]

2Scott Gibson, director of the Center for Preaching at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, as quoted in Terry Mattingly’s “Plagiarism and the Pulpit,” John Mark Ministries; available at http://jmm.aaa.net.au/articles/8844.htm. [Link no longer works]

3Matt Perman and Justin Taylor, “What Is Plagiarism?” Desiring God Ministries; available at www.desiringgod.org.

4Gibson, in Mattingly’s “Plagiarism and the Pulpit.”

[Author credit from 2005] Dean M. Christensen lives in Clovis, California. He is an academic counselor at California State University, Fresno, and a former Christian church minister.

0 Comments