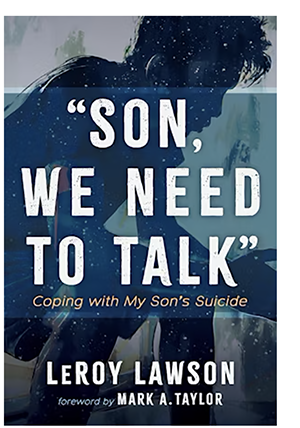

Editor’s Note: We asked Roy Lawson to write the following article upon the release of his new book, Son, We Need to Talk: Coping with My Son’s Suicide, which is available at Amazon.com.

Thirty years ago, on May 26, 1994, Lane Lawson, age 26, took his life following years of debilitating illness and darkening depression. One can only imagine the grief, heartache, and emptiness the Lawson family has felt, and continues to feel, in the wake of this loss. But rather than contain the loss internally, Roy chose to write about it—certainly for his own sake and that of his family, but also for the untold number of families who are dealing with similar losses.

Our prayer is that this article, and the book it’s based on, will give hope and strength to grieving families, provide wisdom and guidance to caregivers and friends, and help those in positions of ministry more effectively love and serve those who are affected by this all-too-common tragedy.

_ _ _

By LeRoy Lawson

Almost 30 years after I first began typing the manuscript, Son, We Need to Talk was released last fall. Just a few weeks ago I returned to the subject of suicide again, this time to write the short article you are reading. To be honest with you, the assignment hasn’t become easier. It isn’t that I can’t think of anything to say; I think of too many things. How can I compress the ongoing emotions, the still unanswered questions, the maddening search for just the right words of advice I’m expected to offer, into a brief essay? The wastebasket beside my desk is full and running over. So many false starts. So many errors in my trials. I even submitted the final copy to friend and former editor Mark Taylor. I knew he’d be honest with me. He was. Discouragingly so. So, I’m trying again.

Here’s what makes it so difficult. It’s not just that each attempt rips off yet another tender scab. People say that you never completely heal from the death of a loved one, and you don’t. You pick up the shattered pieces of your life and go on, sometimes bravely, sometimes fearfully, almost always haltingly. But you go on. “Everybody” knows that, they say, so I don’t need to say so again.

They don’t have as much to say when the subject is suicide. What can they say to the grieving parent whose almost-27-year-old son stole himself from them? To the mother who could read the signs of his growing despair, who was making plans to go to him but didn’t get there in time? To the father who, as fathers are wont to do, wanted so desperately to fix things for his son but could not?

Then there is the church. First the members received the awful news that their pastor’s son had done the inconceivable but now they have to ask the hard questions, not just of their grieving leaders but of themselves: What should we do? How do we help the survivors survive this terrible blow? What do we have to offer after the fact? But perhaps more importantly, how can we be the right kind of church before the fact, because there must be others in our church family who are feeling so desperate that suicide, once so unthinkable, now seems a better option than continuing a life of pain and bleakness? What should we ask the preacher to teach from his pulpit? How should our classes and small groups address this delicate subject? And how do we ensure our church is a safe place for people who otherwise feel misunderstood, judged, depressed, hopeless, and excluded?

Son, We Need to Talk is this grieving father and pastor’s conversation with his dead son. When Lane died, his final loving act while he waited in his truck for the carbon monoxide to take him away, was to explain himself to his loved ones. He scratched out his suicide letter in three-and-a-half pages of tiny lettering. The book contains both sides of a conversation three decades long; he talks first in his final communication to us. Then I answer him. He writes with confidence, at peace with his decision and comfortable with his reasons for it. I am not so sure of myself, either as father or as minister.

Not so sure of myself. If Lane and I were able to talk about his suicide today, I think the advice he would have for his pastor-father and his pastor-father’s church would be just that: Don’t be so sure of yourself. In my public sermons and in our private chats, he was reluctant to interrupt or correct. I spoke with such authority, he thought. But that was then.

Don’t be so sure of me, your son. Lane was quite aware of my fatherly pride—not only in him but in my confidence that suicide is not something he would do. I was very proud of him, and I had a right to be. Handsome, intelligent, athletic, witty, winsome, loving, teeming with charisma—Lane charmed every circle he belonged to. What we did not know until too late was how much pain his smiles masked. He had us all fooled for a long time. We did not see what we could not (perhaps would not) see, that he was running out of the strength and the will to fend off his bouts of deepening depression. In the end, he gave up and embraced death. By that time death had become more to be desired than life, from his perspective the only logical option he had left.

Don’t be so sure of your family. To the Lawsons, suicide was not only unutterable and inconceivable but in both Joy’s family and mine, unprecedented. It just wasn’t done. We belong to the “stiff upper lip” tribe, the people who soldier on even when we want to quit. We applauded—and applied—the adage, “When the going gets tough, the tough get going.” We misled ourselves.

Don’t be so sure of your views on suicide. Here’s where we should have been more alert. While suicide was unknown, chronic depression was not. Several in the family greeted the advent of Prozac with relief. Professionally, since “the show must go on” we all worked to make it happen, often masking health (physical and mental) problems because there simply was no time or room for pampering ourselves. We projected our attitude on others: If we could do it, then they could. Until, like Lane, they couldn’t.

Don’t be so sure of your church’s views on suicide. Many Christians deem suicide an unforgivable sin, because it eliminates any chance to repent and return to God. That makes it a form of murder. It’s playing God, and that’s something God can’t forgive. Fortunately, the church’s stance on suicide has changed over the centuries, and a close reading of Scripture yields the surprising insight: God is still God. We don’t know as much as God does. What we do know leads us to trust God’s grace and understanding and, yes, forgiveness even in situations as dire as suicide.

Don’t be so sure you are right about other people who are different. This is the lesson I want to stress most emphatically. We talk a lot in this politically supercharged era about bubbles and tribes and our propensity to jump to conclusions and to prejudge people who aren’t like us. I’ll be personal here. As a child my Sunday school teachers, who quoted the King James Version, urged us to “judge not, that ye be not judged.” Jesus elaborated, as they did, with some words about “the mote” in my brother’s eye and “the beam” in my own. Ever since, I’ve struggled to get my eyesight—and self-insight—up to Jesus’ standard. I’m still trying.

My father, who didn’t quote much Scripture, reached into Native American lore to admonish: “Don’t judge a man until you’ve walked a mile in his moccasins.” Other adults reinforced Dad’s lessons, undoubtedly after some critical comment of mine. “Remember, when you point your finger at someone else, you have three other fingers pointing back at yourself.” Trite, maybe, but true nevertheless. What they knew but I didn’t yet realize was that I just didn’t know enough to talk so big. You’ve heard it said of someone, “He isn’t always right but he’s always sure.” That was me, I’m afraid. I had to learn it the hard way: “Pride goeth before a fall.”

That “fall” was my son’s suicide. Lane taught me humility. If I could have been so wrong about my own son, bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh; if I could have been so confident that in this most important of all choices—to live or not to live—he was safe, that he would never take his own life, that he had so much to live for and so many who loved him that he would never consider walking away from all of it—from all of us—how then dare I presume to judge anyone else’s mental and emotional state?

So when I’m asked what I learned through my son’s suicide that I would like to pass on to others, especially others in the church, I start with humility. He taught me to listen more and not talk so much. I am far less eager to dive into the theological disputes I once relished, more hesitant to intervene in domestic disputes, afraid of today’s partisan politics in which if you aren’t a noisy belligerent you are considered weak, less ready to dismiss someone for being different, and more, much more, eager to be quiet and know that “the Lord, he is God.”

These days I think often of Jesus’ other words on the subject of judging: “Stop judging by mere appearances, but instead judge correctly” (John 7:24). The people with him, hotly contesting a fine point of religion, were in no mood to listen to anything Jesus had to say. Why should they pay attention to him? After all, “We know where this man is from.” Fateful words, those: “We know. . . . ” Some even accused Jesus of being demon-possessed. They knew. Judging “by mere appearances,” they sized him up and found him wanting. They had already ticked the boxes: He’s from Nazareth (bad), of an unimportant family (bad), teaches religious heresies (bad), lacks proper educational and professional credentials (bad), and hangs out with the wrong crowd (bad). Thus, they categorized and judged and—it was inevitable, since they knew so much—dismissed him.

Do you now understand this important lesson my son taught me? Don’t be so sure you are right about other people who are different. About people who are depressed, or sick, or poor, or marginalized, or in some or many ways unlike you and me. I’ve had so many things figured out, have weighed so many people and found them wanting. Because, you see, I know. I conduct seminars on leadership and management. I pontificate with ecclesiastical authority on so many subjects that don’t matter very much at all. I even hold seminars on marriage and parenting. (“He saved others; let him save himself. . . .”) I have preached more sermons than I can count. I have never been stingy with my opinions. I once could even explain why someone would commit suicide, until I couldn’t.

I didn’t walk away from my calling when Lane died, but for a while I wanted to. It took time to recover, to be slower to judge without grace, learn a new humility—to do my best to love with the love of Jesus. And I have found my own life much more tolerable once I decided to relax and let God be the judge.

To schedule Roy to speak about his personal experience and teach on the topic of suicide, contact him at el2000lawson@yahoo.com.

Beautiful, LeRoy Lawson! I know about losing a child, although I don’t know about suicide. Death took my thirty-year-old daughter from her husband and three little children, and death took Lane from you, his mother and others who loved him. You are so right about grief. It really is never over. As Nell, my wife, always said, “Time does not heal grief, but it does make it softer.” Thanks for this insightful piece with lessons which all of us “old” guys, as well as every younger guy, need to learn. I, too, learned much when our Rhonda left this world. Ever since, I’ve been a different minister when dealing with those grieving. Experience, as the old adage reminds us, is the best teacher. Thanks again for revealing your heart in this article. Your heart has touched my heart.

Thank you for your willingness to remove your mask (like the ones most all wear) and for sharing your raw honesty. Putting yourself out there is huge given the trauma you have experienced. I pray God will use your vulnerability to help others who are struggling and to grow His Kingdom.

Roy, you have always been one of my personal heroes. Again, your article has taught me several key concepts of which I was unaware. Thank you for taking the time, emotional and spiritual energy to pen this article. We love and appreciate you, my brother. God bless you. David Roadcup

One of the things I have learned after 40+ years in ministry and conducting the funerals of a number of young people is “the day the young person died is unique.” It becomes a day like no other, almost like an event. I don’t like the word “event,” but I don’t know how else to describe it. It becomes in some way like a wedding “event.” A day you never want to forget! As the years slip by it does become some easier but a date that you do not want to forget, yet you want to forget. The day of the death of a child is like no other, nothing like the flu, that will soon be forgotten. I’ve often thought “why should I forget.” After all, this was my child. I celebrated this child’s birth and birthdays thereafter. How do I stop? I don’t want to forget my child. I have come to this conclusion: Don’t stop. Remember your child. We remember because we love! We never want love to stop. What would life be without love? We love because He first loved us.

The reminder to “judge correctly” though 2,000 years old is still so needed today. That includes, I think, compassionately as a part of correctly. Thank you for your words of wisdom, LeRoy, in this age of harshness and unkindness.

Roy, Our paths have crossed many times over the years. I have always respected you highly and listened carefully to what you had to say. Thank you for your willingness to share your experience and your insights on this topic that is seldom talked about publicly. Your article and your book will be useful resources for many years to come. I greatly value your friendship as do many, many others. Thank you, Glenn Kirby

Roy Lawson writes a thoughtful, concise summary of his book Son, We Need to Talk. I liked both the book and this summary. Like Roy, I lost a son. My son was 21 when he died; Roy’s son was 26. A couple months ago I had the distinct honor of having two hour-long phone conversations with Roy. They were sweet, sacred talks. Many times we both said, “O dear brother, I am so sorry.” “I can only imagine.” “I so wish it had been different.” “Thank you so much for telling me how this all makes you feel.” … And we laughed, too, saying, “Oh my, I was so certain if I did everything just right all would be just as I hoped.” Mostly, each of us listened, and in listening, realized again this great truth: “If a person feels listened to, he will feel loved. He will hardly be able to tell the difference.” … Roy’s piece emphasizes the idea of not being so sure about all sorts of things of which we once were so certain. Grief can do that, making you not so sure about lots of things, and making you a lot less judgmental–about other people, about other cultures, about other churches of whatever kind, and of course, about how other people do or don’t grieve. I’ve learned to not tell anybody how to grieve. Part of grieving well–and yes, when you lose a child you do walk with a limp (sometimes victoriously, thankfully) the rest of your life–means, however imperfectly, embracing the great tensions in life, and still saying, “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life.” Roy Lawson is among those who do that well.

Lawson’s reflection on his son’s suicide touched me again. I attended his congregation in Mesa when I was out of my own pulpit for a while. I can’t imagine the grief if I had lost either of my sons to suicide. Matthew 5:4 comes to mind, though it seems a bit belated. May God keep comforting LeRoy.

I too lost my 27 year old son to suicide 30 years ago, about 6 months before your son. One of the main things I learned is that mental illness is not something people are educated on. Only in the last few years has there been much more openness on it and opportunities to learn. I plan to read your book. Thank you for sharing. Also NAMI is a really good resource.

Brother Lawson,

Several years ago I read an article you wrote on suicide in the Lookout Magazine. I had several problems with the suicide in April 1980 of my husband Warren A. Sanders, missionary to Colombia, South America. Warren was 44 years old. He had tried several offices of tax people to get advice and he was led to believe he owed a lot of money. He never ever communicated this with me or his Dad or friends. Somehow or other he just decided he couldn´t cope. Brother Lawson, you were the ONLY one to give me comfort. Your article was short but very good. I am so sorry of your loss. Tears are still good and sometimes it helps. God is so very near to us.