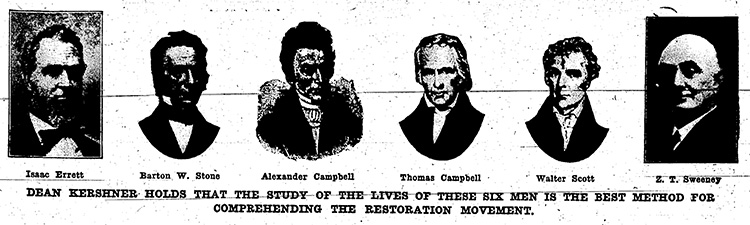

In 1940, Christian Standard published a lengthy series of articles called “Stars” by Frederick D. Kershner, then serving as dean of the School of Religion at Butler University in Indianapolis.

In introducing the series on March 9 of that year, Kershner wrote, “We shall strive to interpret the ongoing of a great movement in the life of the church through the contribution of six of its most significant advocates. . . . We shall be occupied only secondarily with the mere details of biography. . . .”

Those six Restoration Movement “advocates” included:

• Thomas Campbell . . . “who wrote ‘The Declaration and Address of 1809,’ and who laid the foundations for all that followed.”

• Alexander Campbell . . . “his gifted son who carried the thought of his father to its logical conclusion and who made the new movement effective through his forensic ability and his capacity as a writer.”

• Walter Scott . . . “who was the evangelistic pioneer.”

• Barton W. Stone . . . “who shaped the character which the movement assumed in the Middle West.”

• Isaac Errett . . . “who consolidated and gave direction to the early work of the pioneers.”

• Zachary Taylor (Z. T.) Sweeney . . . “the representative of a new period of development in the life of his people.” (Among these six men, Sweeney is the only one with whom the writer had “personal acquaintance,” and Kershner made clear in the series introduction that Sweeney—who died in 1926—influenced him mightily with how he proceeded with this project.)

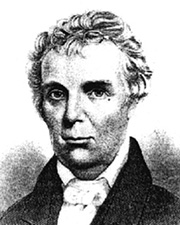

At this juncture, we must decide our direction. Perhaps we should share all 33 parts of this series. . . . On second thought, let’s focus on most of what Kershner wrote about Barton W. Stone, the man behind the Cane Ridge Revival, “The Last Will and Testament of the Springfield Presbytery,” and participant in the handshake that united what many call the Stone-Campbell Movement. Stone’s portion of Kershner’s series ran on April 20, 27, and May 4, 1940. Today we’ll run the first part of the April 20 installment, which is very much an overview of Stone’s life. (The order of Kershner’s original text from April 20, 1940, has been rearranged somewhat.) This will be a four-part series.

_ _ _

“The Message of Barton Warren Stone”

By Frederick D. Kershner

April 20, 1940; p. 7

BARTON W. STONE shares with Alexander Campbell the distinction of being a co-founder of the Restoration movement. There are sections of the country where Stone is looked upon, in certain respects, as a more appealing figure than Campbell. This is especially true in the Middle West, where many of the oldest congregations of the movement were “Stone churches,” and where the allegiance to the Campbells is not as warm and enthusiastic as it is in other sections. Adherents of the new reformation in the localities above indicated objected strenuously to calling themselves “Disciples,” as the sage of Bethany preferred, and insisted upon being styled “Christians” only, in accordance with the approved terminology of Stone. There are certain distinctive features about these congregations which may reflect the personality of the Cane Ridge apostle, and which may therefore be considered as possessing definite biographical significance. If we may judge a tree by its fruits, so we should be able to interpret a reformer by the nature, quality and characteristics of his disciples.

_ _ _

BARTON WARREN STONE was born at Port Tobacco, Md., Dec. 24, 1772, and died at Hannibal, Mo., Nov. 9, 1844. His body was buried at Cane Ridge, Ky., where his work as a reformer had its beginning. . . .

Barton Stone began his early education at Guilford (N. C.) Academy. . . . In 1793, he became a candidate for the ministry, but, having doubts about some points in the Presbyterian theology, he sought employment as a teacher and taught for several years. In 1796, he was licensed to preach, and at the close of that year became minister of the churches at Cane Ridge and Concord, Bourbon County, Ky.

In 1798, he was fully ordained to the ministry of the Presbyterian Church, although he refused to accept the confession of faith without qualification. [At his ordination, Stone told the examining committee that he did not agree with the Calvinistic teaching that a certain number of people were predestined to be saved and that all other people were predestined to be lost; he refused to become a preacher unless the committee was willing to “take him on his own terms” in this much-disputed matter.] . . .

In the spring of 1801, Mr. Stone attended a revival in Logan County, Ky., conducted by James McGrady and other Presbyterian ministers. When he returned to Cane Ridge [Kentucky], he preached a sermon from Mark 16:15, 16. This sermon began a revival which was the preliminary of the great Cane Ridge meeting, perhaps the most extraordinary revival ever held in America. The latter was held in August, 1801. The attendance has been estimated at from thirty to fifty thousand—an enormous audience for such a thinly populated section. Four or five preachers were frequently speaking at the same time in different parts of the encampment, and without confusion. It was at this meeting that the strange physical phenomenon known as “the jerks” was exhibited. Thousands of people professed conversion, and the effect of the meeting was felt all over Kentucky and the Middle West.

At the close of the Cane Ridge revival, an attempt was made to “Calvinize” the converts by an outside preacher. Mr. Stone and others opposed this teaching, and the result was a split. Six preachers—Richard McNemar, John Thompson, John Dunlavy, Robert Marshall, David Purviance and B. W. Stone—withdrew and organized the independent Springfield Presbytery. They published their position to the world in a book called “The Apology of the Springfield Presbytery.” In this work, all human creeds were denounced, and an appeal was made to return to the Bible, and the Bible alone.

Later, it was agreed to dissolve this “presbytery” and to wear no name but “Christian.” Upon this occasion, Stone and his associates published the “Last Will and Testament of the Springfield Presbytery”—a document which ranks in importance in the history of the Restoration next to the “Declaration and Address” of Thomas Campbell.

After breaking with the Presbyterian Church, Barton Stone labored independently at a great financial sacrifice. He worked, like Paul, with his own hands, and had great difficulty in making a living for himself and his family. All the while, he manifested the most beautiful Christian spirit toward those from whom he was separated for conscience’ sake. He wrote, like Robert Burns, while following the plow, and continued his studies under the most unfavorable circumstances. All of the ministers who joined with him in the Springfield Presbytery (except Purviance) forsook him. Nevertheless, he continued to preach and teach, with the result that a large number of churches were won to the new propaganda. One whole Baptist association came over, and “the number of the disciples grew and multiplied.”

In 1824, Mr. Stone met Alexander Campbell, and the two men exchanged their views. There was probably some constraint on both sides; at any rate, nothing definite came of the meeting. In 1831, however, the two men and their followers got together at Lexington, Ky., and agreed to unite. The result of this action was to give an immense impulse to the plea of the Restoration, which from this time on swept like wild fire, not only over Kentucky, but throughout the Central West. . . .

After uniting with the Campbells, Barton Stone continued his work. In 1834, he removed to Jacksonville, Ill. He published a periodical known as the Christian Messenger, a part of the time with John T. Johnson as co-editor. In August, 1841, he was stricken with paralysis, and remained a cripple until his death in 1844.

[Read more about Barton Stone’s early ministry next week.]

0 Comments